Stanislav Kolíbal

* 1925

Stanislav Kolíbal has been a major figure on the Czech art scene since the latter half of the 20th century. Calling his work sculpture is infelicitous when we consider how this type of visual art has undergone fundamental changes in form and meaning in the last fifty years. Indeed, Kolíbal himself has made a major contribution to this transformation both at home and across the world. Concepts such as object or installation, in common use today, are the fruit of a remarkable process systematically nurtured by Kolíbal in his own distinct way since the 1960s. Formal elements – the language of abstraction and geometry, as well as links to minimalist tendencies, conceptualism, process thinking and the Arte Povera movement, are clearly evident in Kolíbal’s work. Nevertheless, it would be a disservice to view them solely in such terms. The artist’s expressive originality lies not only in his pure abstract creativity, which, for example, is one of the assets proclaimed by American minimalism, but also in the ability to sense the content aspect of the works created. This content, though highly philosophical and semantically abstract, touches on the basic premises of human existence.

The decisive break in Kolíbal’s artistic career is considered to be the first half of the 1960s, which opened up collaboration between the artist and contemporary architects and, as he addressed his own artistic problems, shed light on perspectives of abstract language. Kolíbal was attracted to the processuality of abstract sculptures and the issue of the stability, instability, collapse, and convergence of organic and inorganic forms. The temporality of these works is astonishing if we compare output of this kind on the world stage (Richard Serra and Frank Stella). Placing them alongside each other, we also realize the complexity of Kolíbal’s work in terms of both form and content, which is based on an individually and socially construed existential context.

The second half of the 1960s, besides Kolíbal’s extensive output, witnessed two solo exhibitions in Prague, one at Nová síň [New Hall] (1967), the other at the Václav Špála Gallery (1970), as well as the artists unprecedented arrival on the international scene, with contributions to the Scupltures from Twenty Nations exhibition hosted by the Guggenheim Museum in New York (1967) and the Between Man and Matter exhibition in Tokyo, Kyoto and Aichi (1970).

As the 1960s came to a close, the artist’s work focused on the theme of time and its processual nature. He uses reduced abstract form to hint at an analogy to the basic axis of our existence – growth, metamorphosis, extinction. After 1970, however, there was a fundamentally hostile shift in the political situation that, in the visual arts, brought down an iron ideological hand on abstract tendencies and isolated Kolíbal “existentially” in his own studio. Here, literally between the floor and the wall white of his silent, illuminated studio, Kolíbal was forced to choose another type of sculpture, creating, alongside his drawings, reliefs and objects, the legend of the “installation”.

Starting in the second half of the 1970s, Kolíbal was increasingly attracted to illusion and the denial thereof. Geometry remains the foundation, but is used for works which, besides their constructive illusiveness, deal with disrupting and upsetting the seen, where the surface is often finished in a subjective style. Objects and reliefs assume almost metaphorical positions. We can feel the echoes of Kolíbal’s set-design thinking.

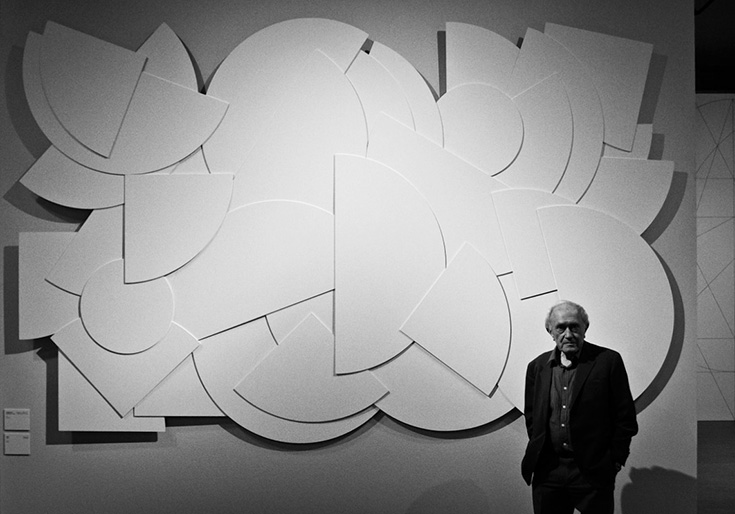

As the 1980s drew to a close, Kolíbal’s work underwent another significant transformation. The decisive catalyst was a DAAD scholarship coupled with a year’s residence in West Berlin in 1988 and 1989. He started producing his Berlin Drawings, in which, through the basic geometric language of lines, circles and intersections, he sought order, harmonious conformity, or the opportunity for conformity. Even here, he did not completely abandon the possibility of fiction, but this was a constructive, traceable fiction, replacing his earlier deconstruction and agitation. Again, in Berlin, Kolíbal expanded into space, with some of his drawings serving as plans for his Constructions, with variable possibilities dictated by the height of the vertical walls. In this respect, Kolíbal noted that the Constructions were “close to an idea that preoccupied him for years – how to express what is merely apparition and what is real”.

From 1990 to 1993, Kolíbal was in charge of one of the studios of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, which had undergone “revolutionary” change. Since the end of the 1990s, in addition to his own work, he has contributed to the installation of large-scale exhibitions, including long-term cooperation with the National Gallery in Prague in the context of its permanent exhibits.

Recently, Kolíbal’s work has embraced relief series, starting with his Black Reliefs. They first were produced in 1999, and were systematically continued in the years 2008 to 2010. Black Reliefs address the issue of layering and make an impact with their contour play on forms and with their matte, signature readable black surfaces. In contrast, his White Reliefs (2011) emphasize geometric drawing, stressing an iron element on a neutral white surface. In a way, they develop the motifs originally seen in the Berlin Drawings and post-Berlin drawings, with their complementary duality of drawing and potential space. Their presence is rendered in the white reliefs by means of subtle relief layering. These drawings form the basis for the large format wall drawings first produced earlier this year at the Zdeněk Sklenář Gallery, space S. The most recent phase of his work is his Grey Reliefs (2012). These, in a way, are a synthesis of the experience and motifs of the White Drawings, as well as objects and reliefs from the 1970s and 1980s, and the preceding two series of reliefs.

Martin Dostál

Exhibitions (selection)

1973 Salone Annunciata, Milan

1979 Walter Storms Galerie, Munich

1980 O.K. Harris Gallery, New York

1983 PAC, Milan

1989 daadgalerie, Berlin

1993 Centre Contemporain, Tours

1998 College of Art, Edinburgh

2000 Deichtorhallen, Hamburg

2005 National Galerie, Prague

Works in public collections (selection)

Albertina, Vienna

Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Metropolitan Museum and Guggenheim Museum, New York

Tate Gallery, London

Collection Lenz Schönberg

Peter Ludwig Museum, Budapest

Museum Sztuki, Lodž

Kunstmuseum, Winterthur

Patentamt, Munich

National Gallery, Prague